A major incident is the stuff of nightmares. Something has already gone colossally wrong, and there is so much potential to make it worse. Reputations and more are on the line and everyone is tense. What is it that differentiates those that handle decision-making during major incidents well from those that foul it up?

Process is Not Enough

Let us assume that the situation in which this crisis occurs is a reasonably professional one. So both the customer and the supplier are aware of and have implemented an ITIL-based incident management process. They also understand that in a major incident, communication is vital to manage the risks. Particularly take care to provide appropriate information to those who must be aware and take containment actions. One organisation with which I worked had a good supplier, but no knowledge of ITIL or application of such a process internally, but this is unusual.

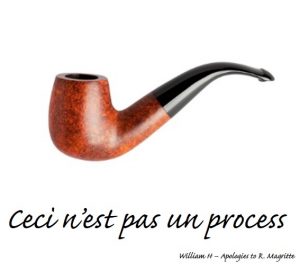

Renee Magritte painted his famous picture La Trahison des images (“the treachery of images”) to call attention to the distinction between the image of an object and the object itself.1 He had fun with the confusion between the title, the image and the habitual ways in which we see the world. In such a way, a documented process is no more a process than Magritte’s picture was a pipe. It is common to encounter services in which the production of such a document is treated as a means to get auditors to go away, being firmly locked where the sun does not shine as soon as backs are turned. If that is your situation, be afraid!

A process is a living, dynamic summary of working relationships and controls. A client who had no faith in their incident management performance asked my team to improve it. This started with an aim: to establish justifiable confidence that operations would provide a high-integrity, reliable service consistent with the needs of the customer and its users. We started with belief. If the process, practice and people’s roles are not in their hearts and minds, you are still in the world of the pipe.

Do not get me wrong; I have nothing against the ITIL processes or associated artefacts such as the Management of Risk.2 Quite the contrary, I advocate them strongly. Just do not stop there. If when the flames are licking, the whole team shares the language and concept illustrated in the process document to work effectively together, you have it right. In case of doubt about your current state, open up a few recent problem tickets. If they clearly state all the following, you are probably on the right track:

- What are the symptoms of failure.

- The areas of functionality that are, and are not impaired.

- Possible causes.

- Tests to identify which of the possible may actually be present and the results of test.

- Resolution plans including who is to do what.

- Progress regularly updated so that the left hand would see what the right was up to during resolution and supervisors can stop and think what is happening.

What the ticket will not show you, but twenty minutes with mouth shut and ears open during a running incident will is the attitude. Is the team energised, focussed, coordinated, urgent but calm, respectful and listening, thinking widely about risks on the horizon as well as dealing with the task in hand? Of course emotions will be running high, but these are people who have to get the best out of each other too.

A good process is not just a series of steps on a piece of paper; it is a practicable approach to get the work done supported by procedures in which the people are trained and confident. This brings confident, practised performance and a common language that minimises ambiguity.

Lessons from Research

A while ago, I met a lively professor by the name of Andrew Campbell. He wrote a text book on strategy that was used in my studies. So when I had a chance to attend one of his seminars on why good people make bad decisions, I jumped at it. He had the germ of an idea, based on research at the time, and was testing it with the audience. This was later published as a Harvard Business Review article with Jo Whitehead and Sidney Finkelstein.3 His interest was the question of why some really smart business leaders make obviously dumb decisions with occasionally catastrophic effects.

Campbell and company decided to look at the processes used by the human brain in making a decision, how this may lead to bad outcomes and what can be done about it. They showed that flawed decisions followed from errors of judgement by key individuals. They then dug into the causes of the misjudgements. When we make a decision, our brains use pattern recognition that is largely hard-wired. Situations remind us of good or bad experience, which strongly influences the development of views. Campbell also identified a mechanism that he called “emotional tagging” that is used to assign significance to information. The conditions that led to inappropriate decisions were the presence of:

- Inappropriate self-interests.

- Distorting attachments.

- Misleading memories.

We cannot rely on leaders to spot and correct for their own misjudgements. The appropriate response is to involve someone else. It is for this reason that in a well-run major incident, with the resolvers working the technical approach, you will see senior managers questioning the consideration of risk and unintended consequences. It is vital that before critical decisions are made, appropriate debate is heard to inform the decision and guard against bias. By doing this in public, the participants are forced to make their thinking explicit, often they are their own best critics. If the outcome is not as hoped for, all have appropriate evidence to show that the process was robust and the advice the best available. This is also reassuring for those in the thick of the fray.

And the Field

Another challenging perspective comes from the army, and in particular the Special Air Service, an elite special forces regiment.4 Floyd Woodrow was a major in the regiment, now retired. He also studied psychology and law, an interesting character. He applies these skills in team and personal development as well as in supporting organisations in crises such as hostage negotiation.

The approach advocated to reach elite levels of performance includes communication, negotiation, intensive personal training and training the team as a unit. As a former soldier, he finds it curious how little training is done in civilian life. Yet we expect our people to work together and perform to a high level! The army will first drill the basics so that all can perform them brilliantly and without thinking even under stress. They become second nature. In an SAS mission, the plan is first thoroughly researched and prepared. All have a voice in its formation (their lives may depend upon it). Ultimately it is the leader who decides on the approach to be taken. They rehearse thoroughly; both generic skills and each individual’s role in the plan. They thus go into battle knowing that the enemy will do whatever they can to disrupt them, but fully familiar with what each colleague will be doing. This makes the unit highly resilient.

During a major incident, decisions must be made that may resolve the fault and restore service rapidly (if all goes well) or compound the crisis if it does not. The actions of airline pilot Chesley Sullenberger over the Hudson River on January 15th 2009 are rightly held up as the epitome of fine action under the greatest pressure.5 He ditched his Airbus A320 safely on the river after a bird-strike disabled his engines. I have seen senior managers make urgent decisions in a crisis of service failure; some have worked, some have not. There is rarely if ever sufficient time to obtain all the information they would like. One resulted in live data being wiped from a disc that was thought to be empty during an attempt to recover from the crash of another in the array. It added days to the recovery.

A while ago, I was asked to conduct an investigation into a major incident that resulted in the failure of a data centre and had not been handled at all well. The incident management people were delightful, but totally unsuited to the role. I sat with them during major incidents: they were totally ignored, having nothing to bring to the resolution. We decided to recruit anew and redeploy the former staff. The new team members went through a thorough selection process, particularly looking for an attitude of organised and urgent thinking to drive faults to resolution. We ended up with quite a diverse group; some highly technical, some young, all with the right attitude. Their leader was a determined Rottweiler, who would never let go and who knew what needed to be done, but lacked managerial graces. We could train for that.

We wrote the case and managed the delivery to ensure that they had the tools they needed to do the job, notably information on the current configuration. We took steps to ensure that this was maintained by information owners to keep it reliable. Their director came in to their training school and gave the most inspiring of leadership talks – powerfully communicating her own passion and belief in the team as setting the new standard. We trained them in problem-solving skills to give them an organised approach and coached them afterwards to identify lessons learned from action.

Without reflection there can be little learning. We helped them to measure and manage their own performance, using lean techniques to keep visual control of the process and its performance. It helps a team and its leader immensely to see what is going on in terms of daily statistics. The job of preparing them is also part of asking “what is going on here?” We trained them in risk management, to look around for unintended consequences before they blow up.

The results exceeded all expectations, not least those of the customer. Average incident duration was reduced by 37 per cent within six months of the new team’s establishment, and breached calls almost disappeared. The team had a fervour and energy about it. They continue to drive their own performance forward, and to inspire their peers. Faults still occur, but with confidence in a thoroughly living and practised process and role, they manage with confidence that is trusted by the senior staff engaged in major incidents. The senior staff now even occasionally do what they are asked when issues are escalated. The process lives, is continually improved is driven forward and works. This pipe is really smoking.

………………………..

References

This article was first published in Outsource Magazine 2013 September 06 and is reproduced with permission.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Treachery_of_Images ↩︎

- https://www.axelos.com/best-practice-solutions/mor/what-is-mor ↩︎

- Why good leaders make bad decisions, Campbell Whitehead & Finkelstein HBR February 2009. Project Delusion ↩︎

- Elite! The secret to exceptional leadership and performance. Floyd Woodrow & Simon Ackland. Elliott & Thompson 2012 ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/US_Airways_Flight_1549 ↩︎