The contract has been signed. Champagne has been consumed. The hangover is over – or is it just beginning? It takes many organisations two years or more to get a new service up and running effectively. In these times of short contract duration, expectations of flick-a-switch cloud services and agile delivery, what can you do consistently to deliver on the promise to users?

Transitioning services from the project environment in which they are developed into live services in which they are operated is fraught with risk. This is particularly so where a former supplier is to depart and a new one takes over the reigns.

Whole-Life Planning

My first exposure to this was not in IT at all. Years ago, I used to be a design engineer. The product delivery process we used required the parallel development of manufacturing and field service with the base machine. It is easy for a designer to shave a few pennies by leaving a burr on a pressed steel part, only to find that in service maintenance, that same burr flays the skin from a technician’s hands. Efficient consideration of whole of life costs and value is essential to efficient design in IT, just as in mechanical engineering. Bad design is frequently inelegant, is unreliable in use, difficult to build and maintain.

IT and other service providers typically organise themselves in groups:

- Those who design and win business

- Those who deliver the change project

- Those who maintain and operate the delivered service.

Resourcing the Transition

When assessing potential providers, customers should to pay particular attention to the transition plans: who has prepared them and who is going to deliver them? Every project organisation has its A, B and reserve teams. Are you getting the A team in your design? If you are, they are likely to be an expensive and scarce resource for the supplier. They should be wary of the “switcheroo” when the genius who has presented departs before delivery. The replacement is likely to be someone who grazes his fists on the ground when walking.

What assurances have you obtained about the continuity of staffing and knowledge transfer? The supplier will want to retain flexibility of resourcing and the ability to economise. Look out for dropped commitments when your procurement people publicly oiling the thumb-screws. Remember, you get what you pay for and there are times when quality is worth it.

Every procurement team will have some form of evaluation of the supplier’s transition planning. For some this is cursory. Conduct a thorough grilling during your assessment, together with the proportionate weighting of scores. If you show that it matters to you, the suppliers are more likely to take it seriously in their design, or show themselves clearly incompetent. Use people on your side who are experienced in service transition and know where the bodies are buried. Ensure you have exposed the vendor’s risk assessment, what they propose to do about it, the degree of residual risk and who bears this. The test approach is particularly important. Planning, resources and objectives for whom. Use your own risk assessment to direct the questioning. Your commercial and operational staff should make sure that the essential transition obligations are reflected in the contract and attend to their delivery.

Project Delivery Teams

There are marked differences in personality type, focus, background and culture between project delivery people and operations staff. There are some who span the two, but they are rare. Project delivery people are used to designing to a brief, wrestling multi-dimensional design problems to the floor and managing cost, quality and schedule. They focus on milestones and products delivered to budget. If something is not on their brief, do not expect them to think about it. They are focussed! Operations people tend to take a broader perspective. They are more interested in end-to-end performance than what their job description says. They are in for the long-haul.

Just over a year ago, I was acting as interim head of IT, and chatting to a project manager delivering a new service that was outside my scope. He struck me as a good, experienced and competent man. I asked him if I could have a look at his plan, which he kindly shared. It made detailed reference to application design, test and vendor selection, but none to service or hand-over to operations. The omissions were swiftly noted and templates were shared as a prelude to plugging the gap. Fortunately, there was time to make amends. The cost was embarrassing but not fatal.

Transition Assurance

Another recent client had suffered a terrible transition when it last had a change of prime supplier. The then-new supplier was a big-name IT outsourcer whom I have seen perform well elsewhere. The experience for this client was less rosy. They described the arrival of the D-team and the pain endured as a series of most basic mistakes and inappropriate assumptions became clear. There was a chasm between this team and the group that had written the proposal. After this, the client’s operations team quite reasonably became rather robust with their project delivery colleagues.

The product of this client’s internal dispute was highly effective.

They hired an experienced service delivery manager. It was his role to produce a set of products to define, validate and deliver the transition from design to live operation. His operational credibility was deep. With brevity and clarity he proceeded to deliver the service design package and the operational acceptance test. He cycled through it repeatedly.

As more of the acceptance criteria were met (such as the delivery of support documentation) his test report progressively moved from red to green. He updated the service design package to reflect the addition. Speaking the language of both operations and projects, he quietly and effectively steered the transition. This was not a one-off event, although there were milestones along it. It was not faultless, but it was done well. Most of the difficulties encountered along the way had been identified long in advance as risks. After formal validation, test and transition to live operations, he continued with the service for some months to bed it in.

Knowledge Transfer

An operations group must have knowledge of a system to support it. This knowledge is likely to combine the tacit and explicit. Most of us who have delivered applications and associated infrastructure are short attention-span types, who like building and enjoy documentation rather less. We generally sell ourselves onto the next job, finding an urgent reason to exit stage-left before starting the drafting of manuals, let alone acceptance that they are good. I am as guilty as many here.

There are some critical disciplines during transition. These are notably deployment, release, knowledge management, validation, test (verification) and change management. Within change management, the area that is often to the fore is that of assessing the impact of change.

Deployment needs to address both the service management perspective of conveying the new service through a controlled series of environments and the people-management perspective of preparing the users and those that support them for new ways of working. One word with two distinct meanings.

Recovering from Disaster

This is not the only way to manage service transition. Another client had taken an energetic and aggressive approach to the separation of one company to two, and the associated separation of their IT estates. The CIO ran on caffeine and cigarettes. The client was nervous of the service, the transition to which had not gone well. The service provider was managing its operations consistently with common practice, given the circumstances. However, their project and transition management appeared to be shockingly bad to the extent that they existed at all.

The client had rejected IT Service Management System for processing requests on the grounds that it did not effectively process any of the core offerings required (e.g. order a new mobile phone). The rejection had been accompanied by the invitation to the service supplier to invoke their plan B. They hurriedly invented a paper-based requests process, not previously having considered contingencies. Requests piled up in authorising managers’ in-trays by the thousand. These were then bulk authorised without review. Breach notices flew. Decisions moved more slowly.

The lack of clarity between service providers meant that incidents repeatedly bounced without resolution. The client’s retained service managers seemed unsure of their role and hesitant in their attempts to resolve it. They hired additional staff to address perceived bottlenecks. This seemed to add to the confusion of role more than the processing of transactions. It was expensive and painful for all. Shining a light on the issues did contribute to a fairly rapid staunching of the blood, but getting it right the first time has to be the better way.

Beware the Cloud on the Horizon

One of the situations that is increasingly problematic is the shadow procurement of cloud services by the business. When done in isolation from the main service provision, this can lead to a last-minute call to the IT department “would you just tie this in to the rest of the service and look after it please?” The immediate answer is frequently “No”. This can be a real problem when IT is ineffective or disjointed from the business. Refusal can be seen as adding to an already poor reputation.1 For this reason if no other, I prefer the approach of taking a sharp input of breath and a declaration “I shall need to assess the impact and come back to you. It will not be quick, and it may not be cheap.”

Suppliers frequently draft cloud contracts to avoid liability and responsibility. Their standardisation of service makes sense, and this helps to contain costs. However, when it comes to getting systems to work together or to provide consistent end-to-end support, there can be some unpleasant surprises. There have been some public failures of cloud services, including data loss and interruption to business. It is IT and commercial managers’ roles to look at such risks in advance and to design support and contingency arrangements appropriately. Handing them a fait accompli is frequently unwise. I have seen this done in a client whose business sidelined an ineffective IT department from a mission-critical systems delivery. The time taken at the last minute to restore the basics was painful.

Governance

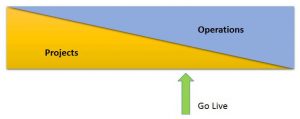

It is natural for project people to conform (at least to some degree) to one type and for operations people to another. However, success requires some over-arching view within the programme governance. It is right for the emphasis to shift over the life of the programme, starting with modest operational representation and ending with a modest project input.

Project / Operations transition effort

Design for operations and transition should start with the earliest development of solution concept. Options that are implausible in transition should not survive the early cull of potential approaches. The obligations here are three-way:

- The Projects group needs to listen to operational input.

- The Operations people need to step up to the mark in providing early and active input.

- The programme sponsor should ensure appropriate balance at all times.

Programme governance approaches such as Managing Successful Programmes take a phase-gate approach to managing delivery.2 That framework contains good practice available to inform assessments of programme health. When it comes to assessing the aspects of delivery specific to transformation, ISO / IEC 20000 Clause 5 provides a good summary of the essentials. ITIL provides a comprehensive set of considerations over hundreds of pages in the Service Transition book.

There is also frequently a need for effective vendor and contract performance management. Many customers neglect these functions until all has gone horribly wrong, then discovering that they have little recourse and a large share of the blame.

An intelligent customer

As in other endeavours, governance takes the central role in allocating resource, in holding providers to account and in setting priorities. The bodies must contain appropriately informed and experienced people who act with diligence and vigour. Their maturity is demonstrated by their asking the right questions and persisting until the answers are convincing. Intelligently assembled data informs good decision-making.3 The sponsor and governance group should ask themselves whether there is justifiable confidence in the people it has appointed to manage the delivery and the approach they have adopted. If not: do something about it! Accountability for appointments is clearly with the Sponsor and Governance.

It is Difficult!

Transition is a complex activity, characterised by the need to coordinate multiple strands and parties. There is good guidance available that can help to validate performance and avoid common errors of omission. This goes a long way to reduce risk to manageable proportions. You will need high-quality people to do it well. Such staff are well worth paying for, as the alternative of picking up the pieces afterwards is truly horrible. Some hangovers do not get better with the passage of time.

………………………

References

A version of this article was first published in Outsource Magazine 17th January 2014 and is reproduced with permission.

- “Mind the Gap!” Business’ Relationship with IT ↩︎

- Managing Successful Programmes, The Stationery Office (TSO), 2011 ↩︎

- Numbers, Numbers Everywhere ↩︎