Methods for delay analysis were largely developed for construction projects. That was fine for IT under waterfall delivery, but the strain is starting to show as agile and other iterative methods dominate. What are the implications for your clients’ projects?

This article designed for IT lawyers is an abbreviated form of the paper “Delay Analysis in Iterative IT Delivery”, published by the Society of Computers and Law. An accompanying podcast is also available at podcast.scl.org.

Traditional Projects and Waterfall

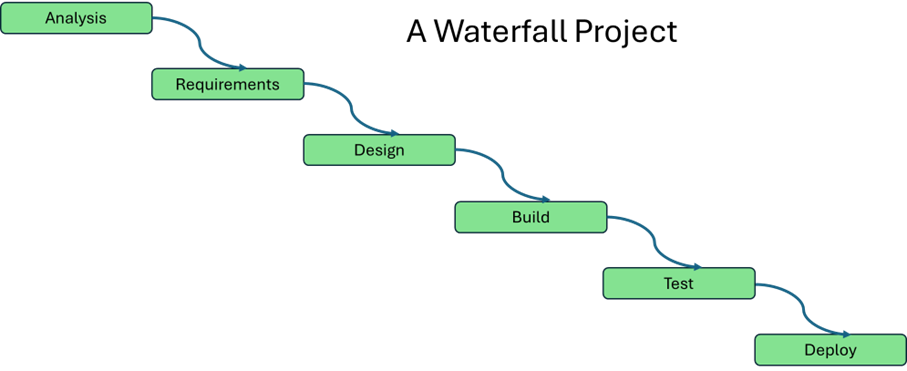

The traditional form of IT project delivery is commonly known as “waterfall.” It follows a series of stages, each being completed before the next starts. There is minimal re-cycling. This method is particularly suited to projects where the requirements are dependable and stable.

Figure 1 – Illustration of a Waterfall Project

This approach is familiar to judges, particularly those who have developed their practice in the construction courts. It is also likely to be comfortable for lawyers. Waterfall project contracts, with schedules full of requirements appear reassuring for their certainty. In practice we know them to be problematic, particularly in the quality of requirements, which can result in late changes to the way the system is required to work.

Established Delay Methods

Established delay analysis methods fall into two classes, both based upon “critical path methods” (CPM). Prospective methods look forward. These are used in the middle of delivery to assess what the impact of a current event is likely to be for final delivery. This is useful for assessing change impact and coming to agreement over the consequences of an incident before moving on to completion. Retrospective methods are used after a project has finished or terminated. They look back over what happened to assess who caused delay, how much is attributed to each party and so to inform calculation of the quantum of loss. Here, discussion is limited to retrospective analysis.

During the delivery of a project, it is normal practice for project managers to gather evaluation and monitoring evidence both to inform their own actions, and to report to senior management in governance of the project. Reports are normally issued at regular intervals. They compare the current state with the plan and raise issues of progress, cost and quality with delivery. These reports, together with plans and tracks of actual build progress, provide valuable evidence for later delay analysis.

In established CPM delay analysis methods, there are several accepted approaches to identifying the critical path through a project at different stages. This can be done for the plan, the contemporaneous prospective view, and retrospectively for the as-built. The paths from each of these is likely to differ from the others. The critical path is the longest path or paths through the programme from either the start, or the point of current examination, to the final delivery event.

The requirements of delay analysis for traditional projects vary slightly by method. The pre-requisites of retrospective CPM methods are generally:

- An accepted baseline plan. The delay analyst uses this to compare plan and actual. The baseline can include approved changes.

- A record of what the delivery team (called “squad” in agile) has built and when critical events were planned and actually occurred. This is frequently captured contemporaneously in software.

- Most require logical linking of tasks to show their precedence and dependency, often captured in the form of a network relationship.

- A record of approved changes.

- A record of actual performance against plan for key tasks or paths. This could be called “productivity”.

Where Agile is Different

Under waterfall, the plan is established at the start, worked to and compared for deviation. The requirements follow the same pattern. Under agile, everything is much more fluid.

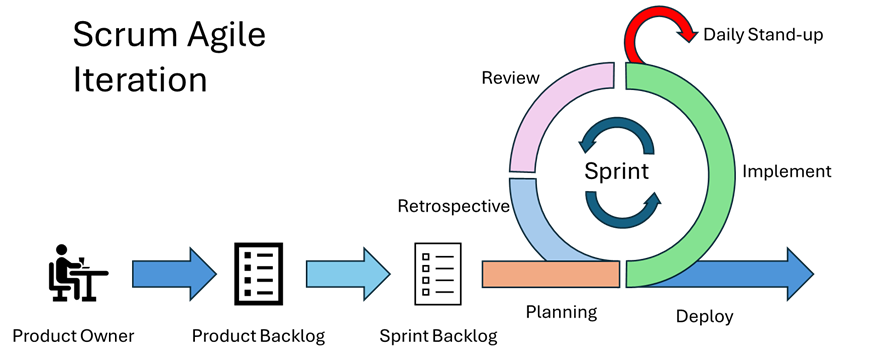

The agile scrum sprint (time-boxed cycle of development) may be illustrated as:

Figure 2 – Illustration of Scrum Agile Iteration

Preparation – This phase is normally undertaken once before the squad starts the first sprint. The complete set of requirements is prepared as stories or use-cases, called a “product backlog.” This is used to inform estimation of total effort, which together with the capacity to deliver it gives the time to completion, delivered through a number of time-bound iterations, called “sprints”.

Sprint Planning – The product owner and squad refine the initial outline sprint backlog before the start of each sprint. The resultant sprint backlog commonly bears a degree of similarity to that originally planned but can see movement due to dependencies and the product owner’s perceptions of value to the customer.

The normal unit of measurement for work in scrum is the “story-point.” This is a comparative measure of effort. A story assigned 2 story-points should be expected to take roughly twice the developer-effort to deliver relative to a story assigned 1 story-point.

At the end of each sprint, there is a review of what has been delivered to assess its quality, and a retrospective meeting to look at progress to schedule and efficiency. These give data as to how rapidly the development is progressing, that can be compared with the initial expectations. There is no schedule of tasks by date order, as there is under waterfall. The assumption is that if the squad delivers work as rapidly as expected, and the total required work does not change, they should be on plan to complete when expected.

What is your Client Really Doing?

Agile and associated iterative techniques are difficult to deploy effectively. Some organisations lack the skill, attitude, commercial or management approach to do so. A hybrid approach is sometimes used to dilute the more demanding requirements of agile whilst preserving use of the label. This may result in “agile in name only.” There are two major areas of interest in relation to this article: change management and task scheduling.

As lawyers you will be interested in change management principally from the perspective of the formal amendment to agreements. That aspect remains under Agile, which is silent on commercial matters. The same controls are normally also applied in waterfall agreements to engineering, requirements and project change. Under agile, they are not. Agile requires this authority to be devolved to the Product Owner on behalf of the customer. Some organisations cannot cope with such autonomy and insist on the application of formal, and frequently time-consuming, change authorisation. Such a hybrid can cause real issues of ambiguity and delay.

Under waterfall, there is detailed scheduling of tasks at the start of the programme and the plan is baselined. Progress is tracked using weekly or other tracks of what has been built. In pure scrum, none of this is done at the level of the task. Agile tends to rely on artefacts such as a database (Kanban) of the stories and tasks to build them that are tracked through states in the sprints to which they are associated. As the data available to the delay analyst is quite different, so the techniques they can use need to adapt too.

Delay Methods for Agile Projects

Traditional methods based on critical path methods do not work at the task-level in pure agile projects because of the absence of many of the pre-requisites to establish the critical path and analyse the difference between plan date and actual execution.

Agile looks to the flow of work, not the date on which tasks occur. Date-based methods therefore sit uncomfortably with analysing agile projects.

The method proposed for analysing delay under agile scrum uses planned rates of flow towards completion:

- The baseline plan for time to complete is based on:

- The project backlog defined for the whole of delivery before the start of development.

- Assumed project organisation into squads. Their relationship, capacity and achievable velocity.

- Consideration of the dependencies, planning tasks within the sprint and ordering these.

- The timing of start and end for each sprint.

- Calculation of the required number of sprints for each squad, hence the planned project duration of development.

- The track of actual to plan is based on the burn-down of actual story-points achieved per squad per sprint. The Kanban record of task delivery supports this with task-level detail.

- The attribution of deviation of actual to plan is based on:

- Analysis of changes in achieved velocity relative to planned.

- Analysis of changed scope relative to the product backlog.

It is here assumed that delay appears in stated project dates through the addition of sprints beyond the baseline plan. Those are each of equal duration. The method seeks to identify which factors were active in requiring this addition, and their relative influence. The analysis reflects the flow characteristics of agile and does not depend on the examination of dates for tasks.

Implications for IT Contracts

The transactional lawyer considering an agile contract should consider:

Change management – This will probably be retained for contract changes. Accept that project and scope change will be handled differently. Limit the risk of expanding scope through capping total story-points.

Scheduling – Expect still to establish major milestones, but not the detail task-schedule beneath. Pay attention to dependencies on other parties as these too may affect delivery.

Governance – Attentive supervision of cost, progress and quality remain vital. Consider data and reporting requirements carefully and ensure the governance body is meaningfully informed throughout. They will need enough data, regularly and intelligently reviewed, to pick up and adapt should the project deviate from plan.

Agile projects emphasise the importance of proceeding at speed. This means that a customer must keep up. If decisive consistency is not your client’s approach, do not try the method, it will probably end badly.

The form of construction contracts has become highly standardised over the years, the interpretation being extensively tested in the courts. This is not so for IT, and particularly not for agile agreements. The requirements of contractual certainty and operational efficiency are likely to be in tension. When done well, governance has a vital role in bridging these objectives in support of skilled delivery staff.

Implications for IT Disputes

Established delay methods were developed principally within construction and have been applied to IT. They are familiar to delay experts, lawyers and specialist judges. Delay and IT experts know their limitations well but have had to work with what is available. The exigencies of litigation combined with the previous lack of a better approach have led to the extensive reliance on judgement in the absence of reliable data.

Conclusions

IT delivery is moving strongly towards iterative techniques across many aspects of operations, not just agile. Their use is therefore likely to grow. Transactional lawyers seek to write good agreements that minimise the risk and maximise value for their clients. It used to be assumed that contractual certainty of scope, requirement and schedule would support this. Under agile techniques, such rigidity may become a millstone around the project’s neck. The nature of risk has shifted. The way to manage that risk must change too.

At the time of writing, the methods proposed here for the analysis of agile projects have not been tested in the courts. They provide what the author believes to be a viable alternative to traditionally established CPM techniques, with the advantage of working within the limitations of agile project data to produce meaningful and replicable results. Until these have been judicially considered, delay analysts and their instructing lawyers may favour the presentation of the new methods, supported by the analysis of a contrary view based on established techniques.

Reference

This article was first posted in Computers & Law and is reproduced with permission. A longer form of this content was published as a paper designed for delay analysts. A discussion of that is available as a podcast from the SCL.